Humor is one of the most potent means of shaping the collective memory for any society. The simple act of sharing a joke, if critically analyzed, can reveal deeply embedded ideological structures. When examined, they expose the way a society negotiates meanings, identities and even histories. Humor as a social phenomenon has the tendency to concurrently unite and divide people. It “produces simultaneously a strong fellow-feeling among participants and joint aggressiveness against outsiders” (Lorenz, 1963). This makes humor a complex phenomenon in a communication setting, which can make it act either as a lubricant or as an abrasive in social settings (Martineau, 1972), which redefines socio-cultural reality (Apte,1985).

Therefore, locating humor in a conflict setting becomes even more complicated to understand considering it functions both as a mechanism of control as well as resistance. Political humor as a means of social criticism or resistance uses humor to delegitimize the mainstream power structure by ridiculing and mocking the elites, privileged and the people in power. In doing so, humor not only plays the part of shifting the power balance towards the less privileged but at the same time also generates a sense of collectiveness amongst the people who ‘share the joke’. On the other hand, humor also functions as a means of social control wherein by assigning what is a laughable act or not, it assigns meanings and values to people, roles and identities. Thus acting as a means of social control. This reasoning is reminiscent of Bergson’s interpretation of humor and laughter as a social corrective: by laughing at something, it is defined as outside of the normal.

Positioning this politics of humor in a conflict setting becomes intriguing. For often, ridicule and disparagement remain the only tools for the oppressed. The Serbian Otpor movement (1998) is a classic example of how political humor was used to drive a civil resistance movement and that too successfully. According to Otpor activist Srdja Popovic, Otpor gained popularity with the people “because I’m joking, [while] you’re becoming angry. I’m full of humor and irony, [while] you are beating me, arresting me, and…that’s a game you always lose, because you are showing only one face, [while] I’m always again with another joke…another positive message to the wider audience”. This subversive quality of humor is often echoed across conflict-protracted regions. Kashmiri Political cartoonist, Mir Suhail when asked about the power of political humor said, “imagine if someone points a gun at you and you respond with laughter. It completely dismisses the existing power structure as something ridiculous.”

Kashmir has a rich history of political humor, which has/is manifested through cultural arts forms like Laddi Shah or ‘through art of controversy’- Political cartoons, as Victor Navasksy would call it. This paper is in essence about locating and understanding the dynamic of humor through political cartoons but specifically directed at, or, through women. However, before moving forward, it is crucial to understand the uniqueness of this construct. First, we are essentially trying to see how political humor legitimizes or delegitimizes the various power structures such as state or society and by doing it in turn assigns meanings, values and identities in the society it is placed. However, when that society, from where it draws humor from, is essentially patriarchal and in addition to that, turns out to be a conflict zone; the meanings, values and identities it negotiates via humor in the form of political cartoons actually become sites for studying double patriarchy.

The culture of political cartooning in Kashmir began around the early 1930’s and the tradition though dwindled still continues today. Using social and political humor in the form of ridicule, irony, and satire via visuals; political cartoons have informed audiences, criticized elites, provided a comical relief and sometimes even instigated violence. Political cartoons have not only been one of the cornerstones of journalism but were also way ahead of their times in terms of laying the foundation of graphic narratives; whose prevalence today marks the dominance of visual culture. Furthermore, they also act as an effective chronicler of the history or rather the essence of times if not the full-fledged acts; which give us the pulse of the society at any given time.

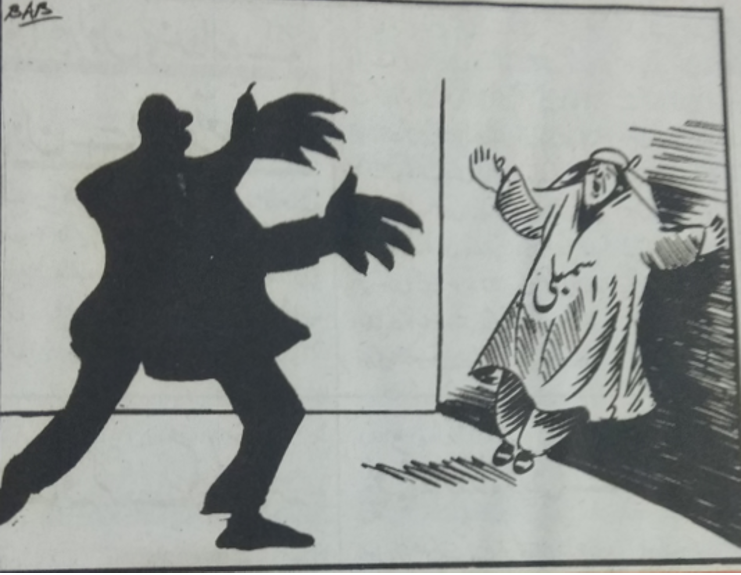

However, if one investigates the representation of women in political cartoons in Kashmir; the results are dismal. Representations of women is a rare phenomenon in cartooning in Kashmir. Cartoons in Kashmir using political humor have been pretty successful and powerful in establishing narratives concerning various aspects of governance, history, culture and even environment. Women have been majorly missing from any major narratives that emerge from the cartoons. In the very few occasions women are subjects of cartoons; majority of them turn out to be sexist in nature wherein to establish a narrative on inter-party politics or the state of affairs; women are often shown through a male gaze- as a commodity or a subject of ridicule. This aspect was also highlighted while drawing the narrative of deep-rooted corruption in the administration; where the reference to the colloquial sexist comment of “Maal” (goods) was also seen to be used by a cartoon correlating bribe with a woman labeled as ‘Maal’ in the cartoon. Further, since political cartoons depend heavily upon visual metaphors; in majority of the cases, women weren’t shown in a direct representation rather women were themselves used as metaphors. For example, in the cartoon below published in 2010 in Srinagar Times, the J&K legislative assembly is shown as a Kashmiri woman, who is about to be attacked by a man (used as a visual metaphor for legislative members).

In another cartoon using the same analogy of the Legislative Assembly as a woman, the cartoon shows a woman trying to cover bare-self from a media camera. Repeatedly, women in political cartoons in Kashmir have been used in an in-direct way, to address a socio-political event where women have no agency or authority. Rather they are used to convey the notions of passivity, helplessness, exploitation. There were a number of cartoons where in order to ridicule key political players or showing the inter-party rivalry; cartoons showed the politicians dressed as women or were shown cooking food. By reducing women to domesticity, they relegated being like a woman or womanhood as something derogatory and not normal.

Cartoons used to create instant meaning within the readers have often used stereotypical representations of women to be the preservers of the culture and purveyors of traditions. Similarly, the gendered notion of work, relegating the house chores to women and physical labor to men; is another way narratives have been built in cartoons using women as subjects.

In most cases, with women subjects -silencing of women in the cartoons occurs by default—they simply have nothing to say—and the pattern of muteness reveals women in Kashmir have no agency of their own. Rather they are mute spectators in a patriarchal setup. Shame, product, and objects are some source domains which were mapped onto giving metaphoric meanings into cartoons using women as subjects. The understanding which thus emerges as women being relegated to a commodity or an artifact meant for decorative purposes or being traded off as objects.

The only exceptions to the sexist representation of women in cartoons have been the female political leaders like Hilary Clinton, Condoliza Rice and Mehbooba Mufti. The latter being one of the major political players of the region got a decent coverage in the cartoons without resorting to any major sexism. However, while representing Benazir Bhutto, former Prime Minister of Pakistan, one of the cartoons ridicules her dressing rather than her political strategy.

It is pertinent to mention that cartoons strive to create an instant impression and understanding with the audiences and as such need to rely on the common understanding of its audiences to be able to connect with them. This gives cartoonists a very small window for experimenting or creatively presenting issues, because priority is given to cartoons reaching to the audiences and as such banking upon stereotypical roles and identities are time and again used in the cartoons at the expense of falling into the trap of sexism/stereotyping. Further, the majority of the cartoons in Kashmir are and have been drawn by men thereby enabling the patriarchal lens through which women have been continuously portrayed.

Additionally, language is something one also needs to address while understanding how women are represented. Considering Urdu language has a grammatical gender, wherein all Urdu nouns are either masculine or feminine; this could shed some light to how and why certain indirect representations majorly used women subjects like representations of electricity, governance, culture and environment. These representations saw these concepts being drawn as feminine or through feminine traits. While one can understand the limitations a language can put into how abstract concepts are/can be drawn; the problematic part arises when the very same language is used to further a certain representation or narrative, which is skewed, stereotypical and sexist in nature. Understanding that electricity is feminine in Urdu language but when that feminine trait portrays electricity as a woman who is being wooed by a man- that is where the problem lies. This has been the chronic case in cartooning in Kashmir.

The real impact of political humor is cumulative. Humor works in subtle and persistent ways. It would be unwise to assume that a single joke or a cartoon will change the public opinion. Collectively, over a period, humor garners the power to tilt the public opinion, to act as a social corrector, reforming using humor. This is what makes laughter so powerful. As it continues to work subconsciously in ways that sharing the sense of humor can reveal group allegiances, communicate attitudes, and help in establishing and reaffirming dominance in a status hierarchy.

Bibliography:

Apte, M. L. (1985). Humor and laughter: An anthropological approach. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lorenz, K. (1963). On aggression. New York: Harcourt.

Martineau, W. H. (1972). A model of the social functions of humor. In J. H. Goldstein, & P. E. McGhee (Eds.), The psychology of humor (pp. 101-125). New York: Academic Press.

Heeba Din is a Lecturer at the Media Education Research Center of the University of Kashmir, where she teaches Human Rights and Photography. She did her Doctorate on Political Cartoons in Kashmir from KU, during which time she was awarded the Maulana Azad Fellowship. She has also received the Kashmir Times Shamim Ahmed Shamin Memorial Award for professional work and academic excellence in 2015. Heeba has also worked as an Assistant Director in the movie “Tamaash” which won the special jury mention at the National Film awards in 2013. She has several research publications in National and International UGC-approved journals to her credit. Her research work includes Emerging Graphic Narratives, understanding the role of Music in Conflict, studying the visual power of Iconic Images, Media and Diasporic identities, Portrayal of Third Gender in Bollywood, and Gender Disparity in local Press in Kashmir. Her current field of specialization and interests are New Media, Comic Journalism, and Cultural Studies.